Being An American playing the Japanese koto…

I used to think that my collaborating with artists from other genres, or incorporating elements from other art forms was something unique to my experience as an American playing Japanese koto in the Bay Area. Upon interviewing and researching these Japanese American cultural artists of the camps, I learned that many of them were doing the same thing from way before, and that incorporating elements and nuances from other art forms is a very American thing to do.

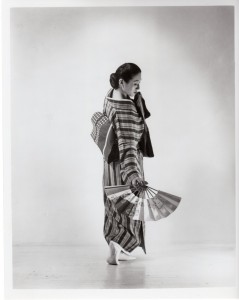

Sahomi Tachibana,

buyo classical Japanese dance teacher at Tule Lake and Topaz,

studied with modern dance innovator Martha Graham,

and applied some of the ideas and techniques she learned in her Japanese buyo dancing. Sahomi attained her “natori” teaching credentials in buyo from the Tachibana dance school.

Sadao Ara, who was a noted Shigin vocal teacher at Manzanar and Tule Lake, studied classical Opera (Ara photo) before the war, and played character roles in many theatrical productions. Ara Sensei used his experience and vocal breathing techniques learned from opera to develop his style and school of Shigin, called Kokusei Ryu (still practiced in the U.S. and Japan). Lily Uematsu, who taught shamisen to June Aochi Berk when she was a young girl at Rohwer, made shamisen more interesting for June by first teaching her “Swanee River” on the shamisen.

Michiko Iseri taught buyo at Heart Mountain.  In the 1956 film version of the “King and I”, she was the consultant for Asian dance to choreographer Jerome Robbins, and played the “Angel” in the ballet “Small House of Uncle Thomas”. One can see definite classical Japanese dance movements in the “Getting to Know You” segment.

In the 1956 film version of the “King and I”, she was the consultant for Asian dance to choreographer Jerome Robbins, and played the “Angel” in the ballet “Small House of Uncle Thomas”. One can see definite classical Japanese dance movements in the “Getting to Know You” segment.

Incorporating styles and ideas from other genres in traditional art forms is a very American tradition…

Then, there is the freedom of expression which was attractive to Japanese American artists. Baido Wakita, Issei (first generation immigrant from Japan) shakuhachi (bamboo flute) teacher and performer, enjoyed the freedom he had in playing any kind of music in the U.S., and with people from other Japanese music schools, something that was discouraged in Japan at that time, and still is, to some extent. His daughter, Kayoko Wakita, became a koto teacher after camp.

I worried that my being trained in the U.S. on the koto would mean I didn’t have a true Japanese feeling in my koto playing. I thought, I am a “yonsei”(4th generation American), so my western viewpoint might be a detriment to traditional koto music. This feeling bothered me for a long time, until I met Kazue Sawai, from Tokyo, Japan, who is the head master of the Sawai Soukyokuin, and a student of famed composer, Michio Miyagi. Kazue Sensei tells her students that she wants them to develop their own sound, and when she hears them play, she wants to be able to hear their individual unique tone.

Because I am an American who plays a Japanese instrument, I realize that I am a product of my influences growing up in Oakland, California, and the diverse music that I have been exposed to: European classical (I played violin as a child), rock & roll, jazz, rhythm and blues, Latin, Middle Eastern, bluegrass, etc. I always look forward to collaborating with artists of other genres, which stretches me and challenges my creativity. I try to work within tradition, but also enjoy exploring new avenues within these new inspirations. Because I live in the diverse San Francisco Bay Area, I’ve been able to collaborate and explore, which is so enriching to me personally. Recently, I came across a 1989 Los Angeles Times article, about Kayoko Wakita, who had similar experiences as a second generation “Nisei”. As a teen-ager at Manzanar camp, she was influenced by piano music, Glenn Miller swing music and tap dancing. Kayoko’s mother was also a koto teacher. Kayoko found koto music to be slow and not much to her liking, until she re-discovered koto after camp, through new music performed by Yasuko Nakashima. Traditional players would say about Kayoko’s koto playing: “Your playing sounds different than anyone else’s,” and she would say, “That’s because it comes from me.” All music goes through changes, and is expressed based on the experiences and background of the individual performer. That’s why live music is always so exciting! It’s the soulful connection you get from communicating with the artist through their art.

The road to “Hidden Legacy” has made me realize that I am just following in the footsteps of the forefathers and foremothers of Japanese American artists who came before me, and who were also influenced by the diverse cultures which we are fortunate to grow up with in the United States. I’m just carrying on in the same American tradition, through Japanese cultural arts, and I will do my best to pass this love of koto music on to the next generation.

Speak Your Mind